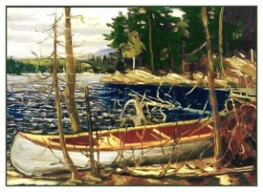

The Jack Pine

The Jack Pine is radically different from the oil sketch on which it is based and is perhaps the dominant contender as Thomson’s greatest work. Although Thomson retains the basic shape of the pine in his oil sketch, he makes the foreground considerably brighter in the canvas. The water surface, which in the oil sketch is hastily laid in with a muddy grey and then a yellowish-grey against the far shore, is transformed into long slabs of pigment in mauves, blues, and yellows, laying down long, unbroken battens of paint one above the other.

This dramatic change is especially evident in the sky. In the sketch, Thomson provides only a rapid swirl of nondescript character, deliberately leaving the wood surface exposed in several places—just as he does in the sketch for The West Wind (1917). In the canvas, however, and even more emphatically than for the lake surface, he dresses the sky in wide, horizontal ribbons of paint. With subtle modulations from the yellow-green sunset clouds at the horizon through to the bluish arc that appears at the top of the painting, Thomson creates a perfect backdrop to the pine and its immediate foreground.

The color of the wood of the small panels has changed since it was milled almost a hundred years ago. When it was new, it was much lighter, possibly even a bright yellowish-white tone if it was of birch. The slow oxidizing over the years has turned the wood into a rich, honey-colored element in the painting and given it a mellow patina.

What is surprising is the immense variety in the colors Thomson summons up for The Jack Pine, an array not seen in the sketch: sumptuous hues, complementing and contrasting light and dark, near and far, minute and grand. Even the softening of the distant shoreline, compared with the harder treatment in The West Wind, takes The Jack Pine into that vivid yet dusky and indeterminate hour of the day that clearly bewitched Thomson.